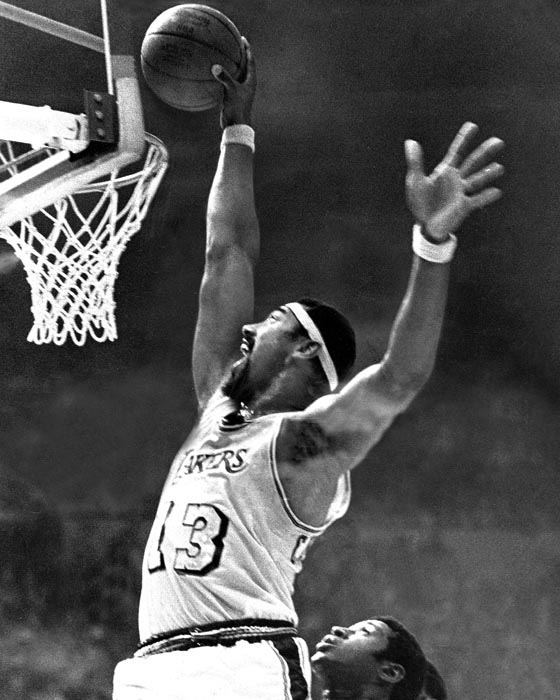

Wilt Chamberlain

Center, #13

- Born Aug. 21, 1936

- Died Oct. 12, 1999

- Attended Kansas

- Coached by Joe Mullaney, Bill Sharman, Butch Van Breda Kolff

The NBA’s first true superstar, Wilt Chamberlain was a dominant figure during his 16-year career. His size and power made him virtually unstoppable around the basket, allowing him to set records that probably never will be broken.

A native of Philadelphia, the 7-foot-1, 275-pound center was an imposing physical force, dominating the inside game to such a degree that he changed the way the game was played, forcing teams to develop more physical defensive tactics. He is the only NBA player to score 100 points in a game or average more than 50 points per game in a season. He won seven scoring and 11 rebounding titles on his way to being selected the league's most valuable player four times.

"I loved the fact that no one could really block my shot," Chamberlain said in an interview with NBA Entertainment in 1996. "I jumped so high that there was nothing that they could do. When you have no fear, it's just going to make you much better at what you're doing."

The Lakers acquired Chamberlain from Philadelphia in July 1968 in exchange for Darrall Imhoff, Archie Clark and Jerry Chambers. Chamberlain grew weary playing for the 76ers after Coach Alex Hannum's departure and threatened to jump to the American Basketball Assn. if General Manager Jack Ramsay did not trade him.

Chamberlain, who preferred "the Big Dipper" among his several nicknames, was still a dominant player when he arrived in Los Angeles at 32. Working alongside Elgin Baylor and Jerry West, Chamberlain developed into a better team player, focusing more on his passing and defense. During the 1968-69 season, he led the Lakers in rebounding, but for the first time in his career was not the team’s leading scorer. Despite meshing nicely with his new teammates, the team continued to fall short of winning a title, losing in the NBA Finals two times over the next three seasons.

Chamberlain preached that winning was more important than individual achievements, and remained adamant that the decrease in the shots he took on the court were because of a conscious decision he made and not a byproduct of tougher defenses or injuries.

"I look back and know that my last seven years in the league versus my first seven years were a joke in terms of scoring," Chamberlain told the Philadelphia Daily News. "I stopped shooting. Coaches asked me to do that, and I did. I wonder sometimes if that was a mistake."

He continued to focus on his rebounding and defensive play, helping the Lakers win a record 33 consecutive games in the 1971-72 season. He then led them to their first title since 1954, putting up a stunning, two-way performance against the New York Knicks despite suffering a broken bone in a hand to earn his only Finals most-valuable-player award.

Chamberlain played his last season in 1972-73, shooting a still-standing NBA record of 72.7% from the field. He also won the rebounding title for an 11th time as an injury-marred Lakers team managed to reach the NBA Finals before losing to New York.

Perhaps sensing the Lakers' best days were behind them, Chamberlain became player-coach for San Diego of the American Basketball Assn. in 1973. The Lakers still had an option year left on his contract and sued Chamberlain, barring him from playing. He helped coach the team before retiring in 1974.

Chamberlain continued to receive offers to play from at least two NBA teams throughout the next decade, but he turned them down. Instead, he focused on his film career and played briefly in a professional volleyball league. He was inducted into the basketball Hall of Fame in 1978 and his jersey was retired by the Lakers in 1983. He died of congestive heart failure in 1999.

Chamberlain, who was never shy about his accomplishments, understood the impact he had on the game.

"I think they had no way to compare what I was doing," he said during a 1996 interview with NBA Entertainment. "It was so far out of the realm of believability. People came to a game and they said 'He's capable of scoring 100 points,' and every night they were looking for 100 points. It had to be very, very special for them to say, 'Wow! Wilt did this or did that,' so 50 points was shrugged off, like, 'Well, he can do that any time he wants.' "

May 20, 2014